A Visual Textile History of Lucknowi Chikan

A Personal Experience..

I have always been partial to Chikan’s work. Something about the gentle craft, the light and shade effect the clothes embellished with Chikan embroidery create, and the classic, seeming simplicity of the motifs that are actually the result of great dexterity with the needle spell powerful, old-world romance. So, in effect, I cannot resist a pretty Chikankari garment.

If over the years, I have been led to believe that the creeper and the paisley were the most popular motifs and that the craft had reached a popular status, but was stagnating, my recent visit to Lucknow sprung a surprise. It was with some eagerness tinged with a cynicism that I stopped at Ada, a somewhat newly opened shop. I had been told about the shop the night before, when I mentioned my interest in Chikankari to a few friends at a party, given in fellow speaker, Shabana Azmi’s honor.

Moments later, someone pointed out the owner of the store, and I was introduced to Vinod Punjabi. A third-generation clothier, he had opened Ada a few years ago, deciding to concentrate on Lucknow Chikan to promote the craft. I was also told that Shabana had visited the store and spent a considerable amount of time there. That, then was why I was worried. Stores visited by celebrities attain celebrity status and get tacit permission to up their prices. I was worried that I was walking into a honey trap, where my greed for Chikan would soon divest me, painlessly of what remaining cash I had on hand. The fact that Panjabi had offered to personally acquaint me with his wares, added to my fears. I was sure I would be expected, encouraged, to shop. Instead, I was given a tour through what can best be described as visual textile history.

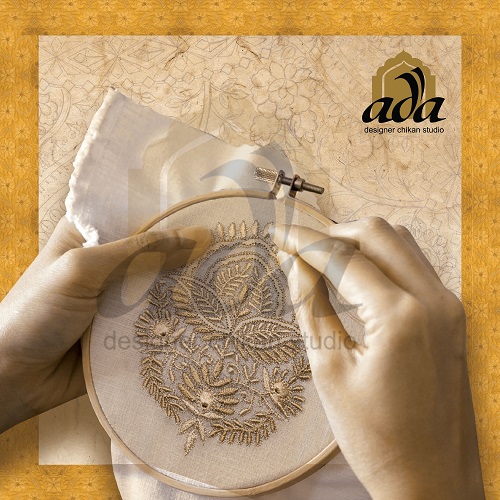

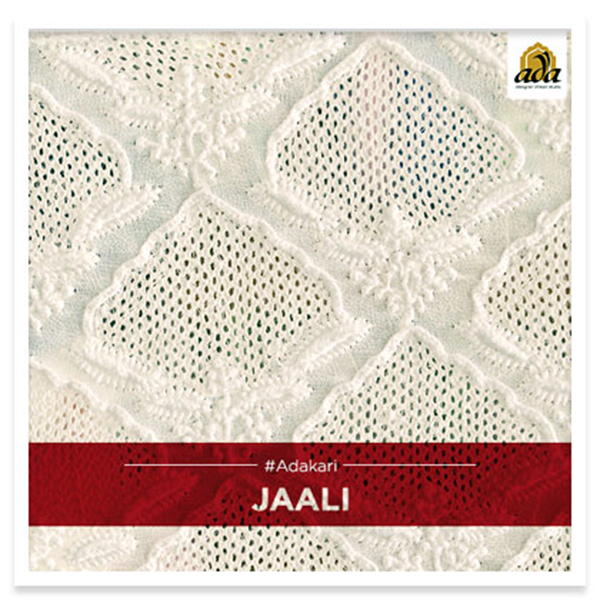

Jaali work done with a single fine thread

Seriously working towards saving the craft and the craftswomen who have been exploited for a very long, Punjabi has invested in a revival movement. The result showed up in the wonderfully embellished range of saris that were classic and breathtaking examples of the heights of perfection Indian needlework can achieve. The usual paisleys and streamers and winding wines were there of course, but the stitches were intricate, and some never before seen, diamond and square motifs had been brought back. Besides the strong Anchor cotton thread that is now used in all chikan work, and can outlast the fabric, there were soft, delicate creations using silk thread. Pinks, blues, and beige worked on with self-colored threads, whispered stories of a bygone era when women wafted past with the rustle of silk and the hint of fragrance, wearing clothes that made them look and feel like princesses, regardless of their real station in life. From bridal wear to evening wear, the story unfolded as piece after piece of visual poetry unraveled. The heavier pieces used lurex for bling, and for zardosi-like work, adding the necessary weight to the sari or cloth length. It was mind-boggling to think of the deft hands and sharp eyes that must have worked ceaselessly to create the perfectly symmetrical and uniform motifs on fabrics as varied as silk, georgette, chiffon, and light as air cotton. But there was more to come.

Chaalu Muqaish and Taarkashi

Marvelous indeed was what was explained to me as the Badla stitch. Looking like a simple stem stitch, the intricate motif has the stem stitch cocooned in silk thread, giving it a raised, rounded feel. A dying art, thanks to the painstaking work involved and the fact that It takes longer than other forms of embroidery. Luckily, Punjabi had located some women who still remembered the craft and given them enough work. And incentivized the younger women who had preferred to work at the meat processing factory, to return to plying their needles to keep the precious knowledge alive and give it a wider clientele. A similar exercise had been undertaken with an embellishment embroidery that went by the name of Kamdani. Gold, silver, and copper were the metallic threads used in a very shiny avatar, to create clothes that shone and twinkled as they caught the light. As the real metal threads would send prices into the stratosphere, plastic thread coated with base metal that mimicked the precious metals were put to use. Special needles were necessary for this craft, and some old needles were fortunately still available, to help in the revival effort. To encourage and support the Kamdani craftswomen, the shop gives them space so they can work in comfort through the day, and consult with older practitioners as the work progresses. The results were precious enough and could rival a starry night without effort. Perhaps the biggest surprise sprung on me was the Daraz-worked linen. Kurta pieces in blue, beige, and other soft colors seemed to have appliqué work in them. Common enough, I thought, as the pieces were opened out. But Daraz is not appliqué. Peculiar to the region around Lucknow, it is created by laying two pieces of cloth in complementary or contrasting colors one on top of the other, marking the geometrical design, and then cutting the design out. But rather than just stitching the cutout pieces, as is done in appliqué, Daraz folds in enough of the cloth under itself before stitching it on, using almost invisible stitches, to get an embossed, latticed effect. Held against the light, the design seems like a veritable fretworked screen.

Various stitches of chikankari done with silk Resham thread and jaali opened by Kasab zari

If there was any thought that lingered in my mind around the real motives behind the revivals, it was cleared as I got answers to my questions. The craftswomen worked as employees, there were workshops where they were given the benefits due to them. Training of younger craftspersons in some of the almost extinct crafts also thus became easier. The value of keeping the crafts alive, as a means of earning for the craftspersons, and as a mission to help save the region’s crafts and also in the process fuel the business by creating benchmarks for workmanship, was the model Ada had decided to follow, and to me, it seemed a very wise and laudable one. So, I was not hugely surprised when told that Punjabi had experimented on combining two popular marketable: Pashmina and Chikankari. After expanding Chikan to fabrics like Chanderi and Maheshwari weaves, both of which gave the embellishment new vocabularies, the experiment with Pashmina seemed natural. Except that by the time the experimenters and craftsperson’s got it right, the concern had spent 17 lakhs! Every Chikan piece goes through at least four washes. To wash away the lines of the block, to wash out the stains of dirt, Haldi, even blood from needle prick accidents that the fabric gathers as the work progresses over days, and some times weeks or months, and finally a wash before it goes to the store. Washing Pashmina with embroidery in silk thread or zari on it proved not just tricky but even seemingly impossible. The wool reacted violently to the varied washes. But finally, the trial and error resulted in success. Today, about two to three pieces of pure chikan-worked Pashmina come ready for sale in a year, and the priceless pieces are worth every rupee of the six-figure tag.

ADA CHIKANKARI FINE EMBROIDERY ON PASHIMA FABRIC SHAWL

I had a flight to catch. Or I would have hung around marveling at the magic unknown, unsung hands had wrought on meters and meters of fabric from so many different sources. Equally captivating was the passion with which Punjabi and his senior staff pursued the revival theme. As I was leaving Punjabi told me that Gulzar Sahab had visited the shop too, and been inspired to write and recite a poem on the spot, at the sight of the wondrous workmanship. Not being a poet of any capability worth noting, all I could say was that I was proud to belong to a country where such art existed, and the visit had been as fulfilling as a walk through a rare architectural monument. I only hope the good work continues on to the next generations too and inspires others in the city to follow the example. And perhaps, other cities can find champions to save their languishing crafts too! After all, it also makes perfect business sense.

Ada launched their website & presence on marketplaces with the aim to diversify into myriad cultures and educate people about Chikan, an art that is unique to Awadh and is not replicated worldwide. Ada aims to deliver this art and experience at the doorstep of all its customers, globally

WWW.ADACHIKAN.COM / 991992003 / 8795160153 / 9775007500